Ahmed Alam

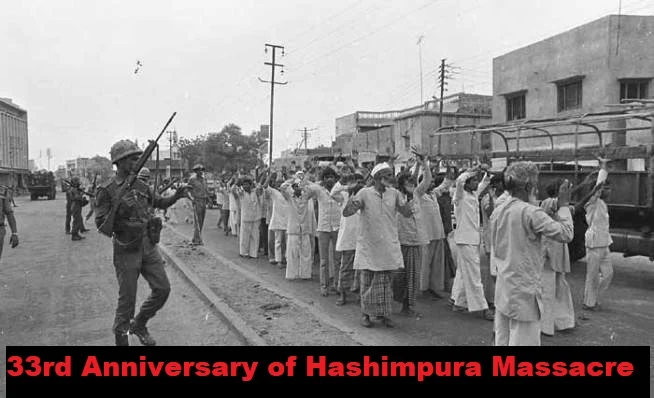

NEW DELHI – The deserted lanes of Hashimpura bore a somber silence on May 22nd, 2024, as the community marked the 37th anniversary of one of the most tragic events in its history. The Hashimpura massacre, a harrowing episode that unfolded on the eve of Jamiatulweda, the last Friday of Ramadan, in 1987, has left an indelible mark on the collective psyche of the residents.

On that fateful day, May 22, 1987, the streets of Hashimpura witnessed unspeakable horror as Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC) jawans ruthlessly gunned down 43 innocent individuals. The massacre, a symbol of government oppression, has become a grim reminder of the perils of communal discord and unchecked state violence.

The Harrowing Events of May 22, 1987

As dusk fell on that fateful Friday, a unit of the 41st Battalion of the PAC descended upon Mohalla Hashimpura, abducting approximately 50 men in a yellow PAC truck. Under the orders of platoon commander Surender Pal Singh, the PAC jawans, numbering 19, embarked on a chilling journey that would forever scar the community.

The abducted men were first taken to Gang Nahar, and then to the Hindon Canal, where the unthinkable occurred. In the darkness of night, the PAC jawans unleashed a barrage of bullets from their .303 rifles, indiscriminately firing upon the unarmed civilians. As bodies fell lifeless into the waters of the canal, the echoes of gunfire pierced the silence, leaving a trail of death and despair in their wake.

Miraculously, five men survived the cold-blooded massacre, their harrowing accounts serving as crucial testimony in the subsequent legal proceedings. Mohammad Usman, one of the survivors, recounted the horror, “After three boys were pulled out and shot point-blank, the others in the truck started screaming, so the PAC jawans opened fire to quieten them.”

The Alleged Motive: A Personal Vendetta?

In the aftermath of the massacre, speculation swirled regarding the potential motives behind the heinous act. S.K. Rizvi, the CID officer in charge of investigating the case, in a note to the Prime Minister’s Office, shed light on one such theory.

Rizvi’s note stated, “It may be pointed out that soon after the incident, there was some speculation in the press that a brother of a locally posted Major Satish Chandra Kaushik had died of gunshot injuries on 21.5.1987 in Mohalla Hashimpura. It is said that as a consequence of this personal tragedy, Major Satish Chandra Kaushik engineered the murder of residents of Hashimpura on the Upper Ganga and Hindan Canals.”

The note further revealed that Deep Chandra Sharma, the father of the deceased, was examined, and he stated that no postmortem was conducted on his son Prabhat Kaushik’s body due to the long delay in the postmortem period.

Vibhuti Narain Rai, a retired Indian Police Services (IPS) officer, in his book “Hashimpura: 22 May,” recounted meetings of top civil, police, and army officials on May 21-22, 1987, during which the would-be killers and those tasked with selecting the victims were chosen. This revelation further fueled suspicions of a premeditated and orchestrated act of violence.

The Long Road to Justice

As news of the massacre spread, minority rights organizations and human rights groups, including the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), voiced their outrage and demanded accountability. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited the city and riot-affected areas on May 30, accompanied by Chief Minister Vir Bahadur Singh.

In 1988, the Government of Uttar Pradesh ordered an inquiry by the Crime Branch Central Investigation Department (CBCID) of the Uttar Pradesh Police. The three-member official investigation team, headed by former auditor general Gian Prakash, submitted its report in 1994, though it wasn’t made public until 1995, when victims moved the Lucknow Bench of the Allahabad High Court.

During the CB-CID inquiry, Sub-Inspector Virendra Singh, then in charge of the Link Road Police Station, stated that upon receiving information about the incident, he headed towards the Hindon Canal, where he saw a PAC truck heading back from the site. When he chased the truck, he saw it enter the 41st Vahini camp of the PAC. Vibhuti Narain Rai, Superintendent of Police, Ghaziabad, and Naseem Zaidi, District Magistrate, Ghaziabad, also reached the 41st Vahini and tried tracing the truck through senior PAC officers, but to no avail.

In its report, the CB-CID Investigating Officer, R.S. Vishnoi, recommended prosecution of 37 employees of the PAC and the police department. On June 1, 1995, the government gave permission for 19 of them to be prosecuted. Subsequently, on May 20, 1997, Chief Minister Mayawati gave permission for the prosecution of the remaining 18 officials.

The Protracted Legal Battle

After the inquiry, in 1996, a chargesheet was filed under Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) with the Chief Judicial Magistrate (CJM), Ghaziabad, who subsequently issued warrants for the accused policemen to appear before the court. Bailable warrants were issued 23 times against them between 1994 and 2000, yet none of them appeared in court. This was followed by non-bailable warrants, which were issued 17 times between April 1998 and April 2000, to no avail.

Eventually, under public pressure, 16 of the accused surrendered before the Ghaziabad court in 2000 and were subsequently released on bail and reinstated in service.

In 2001, after an inordinate delay in pre-trial proceedings at Ghaziabad, kin of victims and survivors filed a petition before the Supreme Court for transferring the case from Ghaziabad to New Delhi, stating that the conditions there would be more conducive. The Supreme Court granted the transfer in September 2002.

However, the case couldn’t start immediately, as the state government didn’t appoint a Special Public Prosecutor for the case until November 2004, though he was later replaced by S. Adlakha, as the former was found to be under-qualified. Finally, in May 2006, charges were filed against all the accused PAC men for murder, conspiracy to murder, attempt to murder, and tampering with evidence, and the trial was scheduled to begin in July.

On July 15, 2006, the day the trial was to begin, it was deferred to July 22 by Additional Sessions Judge N.P. Kaushik of the Delhi Sessions Court, after the prosecution said authorities in Uttar Pradesh had yet to send important case material to Delhi. Kaushik also issued notices to the Chief Secretary and Law Secretary of Uttar Pradesh, seeking an explanation for the delay.

When the trials began on July 22, three of the 19 original accused, including platoon commander Surender Pal Singh, under whose instructions the massacre was allegedly committed, were already dead. Additionally, it was revealed that the rifles used had already been redistributed among the jawans of the 41-B Vahini Battalion of the PAC, after forensic analysis by the Central Forensic Science Laboratory (CFSL) in Hyderabad.

By May 2010, 63 of the 161 persons listed as witnesses by the CB-CID had been examined. On May 19, 2010, four witnesses, including Sirajuddin, Abdul Gaffar, Abdul Hamid, and the then Officer on Special Duty (OSD) Law and Order, G.L. Sharma, recorded their statements before Additional Sessions Judge Manu Rai Sethi at a Delhi Court. However, none of the eyewitnesses could recognize any of the accused PAC personnel.

On October 16, 2012, Janata Party president Subramanian Swamy moved the Delhi court, seeking a probe into the alleged role of P. Chidambaram, the Union Minister of State for Home Affairs at the time, in the massacre.

Acquittal and Appeal

In a shocking turn of events, the Tis Hazari Court, a district court in Delhi, acquitted all 16 of the accused in the Hashimpura massacre case due to insufficient evidence, underlining that the survivors could not recognize any of the accused PAC men.

Hashimpura Massacre: A Long-Awaited Reckoning

The Uttar Pradesh Government challenged the trial court’s order acquitting the accused in the Hashimpura massacre case. The government appealed the decision in the Delhi High Court. Sh. Zafaryab Jilani, Additional Advocate General, spearheaded the case, with assistance from Ram Kishor Singh Yadav, Additional Advocate General at the Supreme Court. Mr. Kaushal Yadav, Advocate-on-Record, served as the Public Prosecutor in the matter.

After a prolonged legal battle spanning decades, a critical breakthrough emerged on October 31, 2018. Retired police officer Ranvir Singh Vishnoi, 78, produced the police general diary as pivotal evidence before the Delhi High Court. This crucial piece of evidence proved instrumental in overturning the trial court’s verdict, leading to the conviction of 16 personnel from the PAC and their sentencing to life imprisonment.

Aslam Chaudhari, a witness to the tragic events, solemnly reflected, “For 37years, the Eid of Hashimpura has been mourned. In 1987, on May 22, the massacre occurred on Jamiatulweda, claiming the lives of 43 innocent souls, whose blood-stained clothes bore testimony to the brutality unleashed upon us. My own brother fell victim to this senseless violence. The paltry compensation offered by the government serves as a stark reminder of our ongoing struggle for justice.”

The journey towards justice for the victims of Hashimpura has been arduous, marked by perseverance and resilience. The landmark verdict delivered in November 2018 finally held the perpetrators accountable, with PAC jawans implicated in the atrocity sentenced to life imprisonment.

According to some legal rights activists, this prolonged delay was a calculated tactic to benefit the accused.

Senior Advocate Vrinda Grover, who fought the case on behalf of the victims, vehemently condemned the delaying tactics. She narrated how a fair, rigorous, and impartial investigation was systematically thwarted at every stage. Crucial pieces of evidence, both documentary and ocular, were either not collected, destroyed, or allowed to disappear. Grover asserted that this was not an accidental lapse but rather a premeditated omission and criminal negligence designed to dilute the prosecution’s case and shield the accused.

However, Advocate Grover emphasized that they were able to present sufficient circumstantial evidence and official records identifying and naming the accused as the PAC men responsible for the murders. She stressed that the identity of the Hashimpura killers was no mystery and could have been easily uncovered from official records and interrogations of senior PAC officials and other police officers. The trajectory of the investigation, she argued, was collusive, corrupt, and intended to shield and protect the accused.

Islamuddin, a steadfast advocate for justice, has been at the forefront of the community’s quest for closure, tirelessly championing the cause of those slain by PAC bullets.

The scars of the past are not merely metaphorical; they are etched into the very fabric of Hashimpura. Bullet-riddled walls stand as silent witnesses to the horrors endured by its inhabitants. Despite the passage of time, the trauma lingers, casting a long shadow over the community’s collective psyche.

M Ansari, a survivor of the massacre, bears physical remnants of that fateful day, with bullet marks still visible on his back. Recounting his ordeal, Waseem shared, “I lay breathless, as bullets tore through the air. The PAC demanded that students raise their hands, only to mercilessly gun them down. It was my testimony that played a pivotal role in securing justice for the victims.”

Beyond the physical scars, Hashimpura grapples with the psychological toll of the massacre. Educational pursuits are viewed with skepticism, as the specter of unemployment looms large. Despite the strides made in the pursuit of justice, a sense of disillusionment pervades the community, with many feeling that true accountability has remained elusive.

Mohammad Aqil , reflecting on the enduring impact of the tragedy, remarked, “While the current lockdown is a necessity in light of the pandemic, it pales in comparison to the lockdown imposed upon us 37years ago. Every Jamiatulweda serves as a painful reminder of our collective trauma.”

The Hashimpura massacre stands as a stark reminder of the perils of communal discord and unchecked state violence. As the nation grapples with the complexities of its past, the quest for justice for the victims of Hashimpura serves as a beacon of hope, a testament to the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

The legal odyssey spanned over two decades, with multiple pivotal moments:

- A chargesheet was filed on May 20, 1996.

- The Supreme Court transferred the trial from Uttar Pradesh to Delhi in September 2002.

- Charges were framed against the accused PAC men for murder and criminal conspiracy in May 2006.

- Survivor Zulfikar Nasir gave evidence in court as Prosecution Witness No. 1 on September 4, 2006.

- The current Special Public Prosecutor was appointed in February 2008.

- The last prosecution witness was examined on December 8, 2011.

- Prosecution evidence was closed in 2014.

- Statements of the accused were recorded on May 23, 2014.

- Defense evidence was recorded on August 6, 2014.

- Final arguments were heard from August 13, 2014, to January 8, 2015.

- The judgment was pronounced on March 21, 2015, acquitting all the accused.

- The Delhi High Court overturned the trial court order, convicting 16 accused in 2018.