By Anwarulhaq Baig

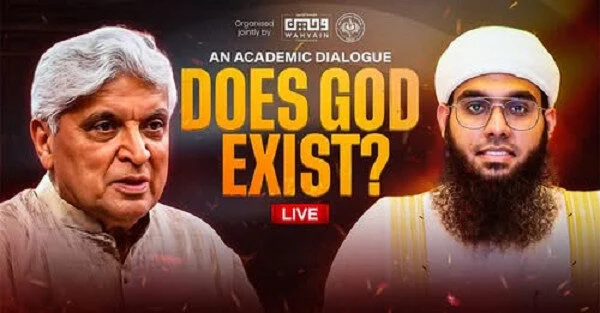

A debate on the existence of God was recently held on The Lallantop YouTube channel between Mufti Shamail Nadwi and the renowned film screenwriter and lyricist Javed Akhtar. The discussion was ably moderated by the well-known journalist Saurabh Dwivedi.

Such debates are truly commendable and meaningful initiatives, as they serve as effective platforms for conveying ideas of truth to both the general public and intellectual circles. Preparing and nurturing the younger generation intellectually, academically, and morally in this manner is one of the most pressing needs of our time.

In this context, the young scholar Mufti Shamail Nadwi presented a serious, reasoned, and dignified discourse on the existence of God, skillfully weaving together philosophy, rational argument, and insights from modern science into a coherent narrative. Although the debate was not a decisive “win-or-lose” encounter, the rational strength of the case for God’s existence clearly outweighed the weak and hollow arguments advanced from an atheistic standpoint.

During the discussion, Javed Akhtar relied largely on rhetorical expressions and conceptual ambiguity rather than substantive philosophical reasoning. He attempted to divert the debate toward emotionally charged questions, such as: If God created everything, why did He create evil? Why does evil exist within the system God Himself created?

Mufti Shamail Nadwi responded with a simple yet effective analogy. In an examination paper, both correct and incorrect options exist. If a student selects the wrong option, the fault lies with the student, not with the examiner who prepared the paper. Similarly, God created both right and wrong and granted human beings free will. When a person chooses wrongly, that choice is the individual’s own responsibility, not the Creator’s.

Javed Akhtar then raised another emotionally charged question: If God exists, why are children dying of hunger and war in Gaza, and why are innocent lives being lost in other parts of the world? While deeply troubling, these questions are emotional rather than philosophical in nature. The core issue highlighted during the debate was that atheism often rests on emotional reactions and assertions, whereas belief in God is grounded in reason, logic, and structured argumentation.

During the discussion, complex philosophical and scientific concepts such as the Contingency Argument and Infinite Regress were mentioned. Mufti Shamail made sincere efforts to clarify these ideas in accessible terms. But no single debate can cover such profound topics. Moreover, discussions on divinity involve concepts and terminology so intricate that they often surpass the grasp of ordinary audiences. Therefore, it becomes necessary to explain these ideas through simple examples and continued reflection.

The Contingency Argument and What Is Contingency?

The term contingency refers to dependence or conditional existence. A contingent being is one that:

- Does not exist by itself

- Is not independent in its essence

- Requires external support or explanation to exist

Philosophically, a contingent being is something that could have existed or not existed.

Everyday Examples:

- A human exists → because of parents

- A tree exists → because of seed, water, and soil

- A house exists → because of a builder

- A car exists → because of a factory and craftsmen

None of these exist by necessity. Their existence depends on something else.

What Is the Contingency Argument?

The Contingency Argument can be summarized as follows:

- Everything in the universe, including the universe itself, is contingent.

- A contingent being cannot explain its own existence.

- An infinite chain of contingent explanations cannot ultimately explain existence.

- Therefore, there must exist a non-contingent, necessary being that explains the existence of all contingent beings.

This necessary being:

- Exists by itself

- Depends on nothing else

- Explains why contingent beings exist

This being is called God.

Historical Origin of the Contingency Argument:

- The argument was first presented clearly and systematically by Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037).

- Earlier, Aristotle (384–322 BCE) discussed causality in metaphysical terms but did not fully develop the contingency framework.

(Reference: Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book XII) - Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) transmitted and popularized the argument in Western philosophy through his “Third Way.”

(Reference: Summa Theologica, I, q.2, a.3)

Infinite Regress: Meaning, Definition, and Criticism

Infinite regress is an endless chain of dependence:

Cause → cause → cause → … without end

If every explanation depends on a prior explanation, then no final explanation is ever reached.

Simple Example:

Imagine standing in a queue at a ticket counter, but the line is endless.

Question: Will your turn ever come?

Answer: No.

Likewise, if causes never terminate, nothing could ever occur.

Infinite Regress Applied to Existence

- You exist → because of your parents

- Your parents exist → because of their parents

- This chain extends backward to the universe

If…

- The universe was created by God

- God was created by a super-God

- That super-God was created by another greater God

and this chain were infinite, you would never exist. But you do exist. Therefore, the chain of causes must stop somewhere.

Why Infinite Regress Fails

- It never provides a complete explanation

- It violates the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR)

- It makes the existence of the present impossible

Thus, infinite regress cannot explain reality.

The Necessary Being (Wājib al-Wujūd)

Philosophy calls the stopping point of contingent dependence the Necessary Being.

A Necessary Being:

- Exists by itself

- Depends on nothing else

- Must exist—its non-existence is impossible

If such a being did not exist, nothing else could exist.

This Necessary Being is called God.

Objection:

If everything has a cause, then God must also have a cause.

Response:

The Contingency Argument does not claim that everything has a cause.

It claims that everything that is contingent has a cause.

A contingent being is one whose existence is not necessary—it could have existed or not existed—and therefore depends on something else for its existence.

God, however, is not contingent. God is understood as:

- Non-contingent (necessary) — His existence does not depend on anything else

- Self-existent — He exists by His own nature

- Independent — He requires no external explanation or cause

Because causation applies only to contingent beings, it does not apply to a necessary being.

Therefore, asking “Who caused God?” is a category mistake—it wrongly applies a rule meant for contingent entities to a necessary one.

This is similar to asking:

“What color is the number five?”

Numbers do not belong to the category of things that have color, just as a necessary being does not belong to the category of things that require causes.

Response: Problem of Infinite Regress

The Contingency Argument replies that:

- If the chain of causes is not brought to an end,

- An infinite regress necessarily follows,

- And such an infinite regress cannot provide an ultimate explanation.

Therefore, reason requires that the chain of contingent causes must terminate in a being that does not require a cause—a self-existent, necessary being, which is what is meant by God. The argument does not claim that everything has a cause; it claims that everything contingent has a cause—and God is not contingent.

What Do Classical Philosophers Say?

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, c. 980–1037)

- Introduced the fundamental distinction between contingent beings (mumkin al-wujūd) and the Necessary Being (wājib al-wujūd)

- Argued that contingent beings cannot account for their own existence and therefore require a Necessary Being

- Identified God as the metaphysical foundation of all existence, upon whom all contingent beings depend

Reference: al-Ilahiyyat (The Metaphysics)

Imam al-Ghazali (c. 1058–1111)

- Rejected an infinite regress of causes as logically impossible

- Argued that if past events had no beginning, nothing could ever occur in the present

- Concluded that a First Cause must exist

Therefore, God is eternal, uncaused, and necessary.

Reference: Tahafut al-Falasifah

Ibn Taymiyyah (1263–1328)

- Allowed the possibility of an infinite regress of past events

- Rejected an infinite regress of ontological dependence

- Emphasized God as the continuous sustainer of existence, not merely a first temporal cause

Analogy: Many light bulbs may exist, but without a power source, none can remain lit.

Reference: Darʾ Taʿāruḍ al-ʿAql wa al-Naql

Allama Iqbal (1877–1938)

- Criticized traditional contingency arguments for reducing God to a mechanical “First Cause”

- Emphasized God as a Living, Dynamic, and Creative Reality

- Argued that reason points toward God, but religious experience completes human knowledge of Him

Reference: The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam

While these thinkers differed in emphasis and method, they broadly agreed on one central point: Contingent existence ultimately depends on a reality that is necessary, self-subsistent, and independent. They differed not on whether God exists, but on how best to understand God’s relationship to the world.

Objections to the Contingency Argument and Their Responses

Several modern Western philosophers have challenged the Contingency Argument. Below are the most influential objections, along with standard philosophical responses.

- David Hume (1711–1776)

Hume’s Objection

- Even if every individual thing in the universe has a cause, it does not follow that the universe as a whole requires a cause.

- Hume famously asked: “Why can’t the universe just exist as a brute fact?”

In simple terms: If every brick has an explanation, that does not necessarily mean the entire wall needs a separate explanation.

Hume therefore rejected the need for a Necessary Being.

Reference: Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

Response:

This objection misunderstands the Contingency Argument. The argument does not claim that everything has a cause; rather, it claims that every contingent being requires an explanation.

The universe itself is contingent—it could have existed or not existed. Explaining the parts of a contingent whole does not eliminate the need to explain the whole itself. The “wall made of bricks” analogy fails because the wall itself remains contingent, regardless of how well its parts are explained.

- Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

Kant’s Objection

- Human reason cannot legitimately go beyond possible experience

- A “Necessary Being” is merely a concept, not something whose existence can be proven

- The Contingency Argument, Kant argued, secretly depends on the Ontological Argument, which he rejected

In simple words: We cannot logically move from “things require causes” to “God necessarily exists.”

Kant rejected the argument on philosophical, not religious, grounds.

Reference: Critique of Pure Reason

Response:

Classical Islamic philosophy clearly distinguishes between:

- The Ontological Argument, which argues from concepts alone

- The Contingency Argument, which begins from actual existing reality

The Contingency Argument does not infer God’s existence from a definition or concept, but from the undeniable existence of contingent beings. Therefore, Kant’s objection does not directly apply to this form of the argument.

- Bertrand Russell (1872–1970)

Russell’s Objection

- The universe does not need a reason

- He famously stated: “The universe is just there, and that’s all.”

In simple words, not everything needs an explanation, perhaps existence itself is simply a brute fact.

Russell rejected the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR), which is central to the Contingency Argument.

Reference: Why I Am Not a Christian

Response:

This position effectively abandons rational inquiry. If “it just exists” were an adequate explanation, then science, philosophy, and reasoning itself would lose their explanatory force.

Classical philosophy maintains that whatever could possibly not exist requires an explanation. The universe has not been shown to be eternal or necessary. Labeling it a “brute fact” avoids explanation rather than providing one.

- Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900)

Nietzsche’s Objection

- Rejected metaphysical absolutes

- Viewed God as a psychological or cultural construct rather than a logical necessity

- Dismissed arguments like contingency as life-denying abstractions

Reference: The Gay Science

Response:

Nietzsche offers a psychological critique, not a logical refutation. Explaining why people believe in God does not show that the belief itself is false. A belief motivated by fear or hope can still be objectively true. Thus, Nietzsche dismisses the argument rhetorically but does not refute it philosophically.

Contemporary Western Defenders of the Contingency Argument:

Alexander R. Pruss (b. 1973)

In The Principle of Sufficient Reason, Pruss rigorously defends the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR).

PSR states: Every contingent fact or being has a sufficient reason for why it exists rather than not.

Why this matters:

- It grounds the claim that contingent beings require explanations

- Rejecting PSR leads to arbitrariness and explanatory collapse

- Science, logic, and everyday reasoning already presuppose PSR

- Without PSR, questions such as “Why does the universe exist?” become meaningless

In short: Pruss justifies the rule that contingent things require explanations.

Edward Feser (b. 1968)

In Five Proofs of the Existence of God, Feser clarifies the metaphysical nature of God.

He shows that God is:

- Necessary

- Uncaused

- Pure actuality

- Independent of all conditions

Feser explains why the question “Who caused God?” is a category mistake, not a serious philosophical objection.

Within the Contingency Argument:

- The explanatory chain must terminate in a non-contingent being

- God is not one object within the universe

- God is the ultimate explanation, not something needing explanation

The Contingency Argument demonstrates that:

- Contingent beings cannot explain their own existence

- Infinite regress fails to provide an ultimate explanation

- A self-existent, independent, and necessary being is required

Despite criticisms from some Western thinkers, the core insight of the argument remains philosophically strong: If contingent beings exist, a Necessary Being must exist. This Necessary Being—eternal, independent, and self-sufficient—is what classical and contemporary philosophy mean by God.

The central point of the Contingency Argument is that whatever is contingent cannot bring itself into existence; it requires a sufficient reason. This is where the problem of infinite regress arises. If every contingent thing is explained only by another contingent thing, and this chain extends infinitely backward, then the fundamental question—“Why does this exist?”—is never truly answered.

This reasoning is directly connected to the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR), which states that everything that exists must have an adequate explanation for why it exists and why it is the way it is. If causes form an infinite regress, then no ultimate explanation is ever provided, resulting in a violation of PSR. Reason therefore demands that the chain of causes must terminate in a being that itself requires no cause—whose existence is necessary in itself. Such a being halts infinite regress, fulfills PSR, and renders the existence of the universe intelligible. Hence, classical theology concludes that the existence of an independent, eternal, and self-sufficient being is rationally unavoidable.

What does the Quran say?

The Qur’an poses a powerful rational question: “Were they created by nothing, or were they themselves the creators?” (Surah At-Tur, 52:35)

This verse presents only two possibilities to reason—and rejects both:

- The universe came into existence without a cause (impossible).

- The universe created itself (absurd).

By rejecting both possibilities, the Qur’an directs human reason toward a third and unavoidable conclusion: there must exist a Creator who is uncreated, self-sufficient, and the ultimate cause of all that exists.

The Quran further states:“Allah is As-Samad (the Self-Sufficient; all depend on Him).”(Surah Al-Ikhlas, 112:2)

Thus, the Contingency Argument, and Qur’anic reasoning converge upon the same rational conclusion: a necessary, eternal, self-sufficient, and supreme being exists, and that being is God.

Conclusion :

For decades, sections of the film industry have sought to promote atheism, scepticism, and a critical attitude toward belief in God. Javed Akhtar has played a prominent role in advancing atheistic and irreligious themes in cinematic culture, often attempting to marginalize faith and remove God from the popular imagination. Under such influence, many film personalities—and even some Muslim actors—have adopted similar outlooks. In this way, cinema has, at times, consciously contributed to distancing the younger generation from faith, particularly from belief in God, Islam, and moral truth. However, this influence is now weakening. The new generation is no longer persuaded by slogans or rhetorical assertions alone; it responds to reasoned and coherent arguments. And when reason is pursued honestly and consistently, it ultimately leads to the recognition of God’s existence. God willing, through scholarly, dignified, and well-reasoned debates and discussions, the message of truth will reach every home and every individual—no matter how dazzling falsehood may appear.