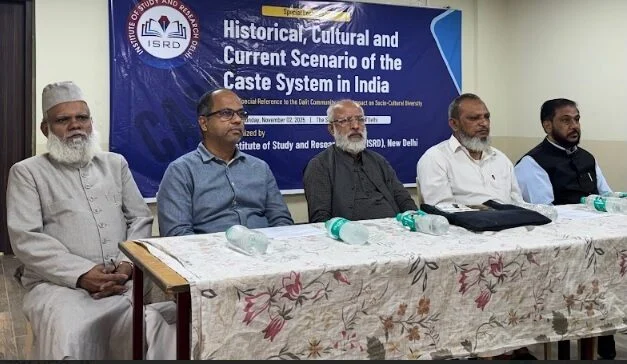

New Delhi: The Institute of Study and Research Delhi (ISRD) organized a programme under its lecture series at Scholar School Hall, Abul Fazl Enclave, Okhla, titled “The Historical, Cultural, and Contemporary Context of the Caste System in India: With Reference to the Dalit Community.” Sociologists and scholars shed light on the caste system in Indian society, emphasizing that although legislation and education have somewhat reduced its impact, the roots of caste remain deeply embedded in the social mindset.

Jamaat-e-Islami Hind (JIH) Secretary Dr. Mohammad Raziul Islam Nadwi, in his presidential address, stressed that the caste system cannot be eradicated until the mindset changes. He clarified that the notion of caste among Indian Muslims is not part of Islamic teachings but rather a social influence inherited from the broader Indian context. He said that while caste in Hinduism has a religious basis, Islam has no such concept — among Muslims, it is purely a social construct.

Dr. Nadwi elaborated that Islam stands for absolute equality, citing the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ who declared that no Arab has superiority over a non-Arab, nor a white over a black — superiority is based only on piety (taqwa). Referring to the example of Hazrat Bilal (RA), he noted that when Makkah was conquered, a black former slave was asked to give the call to prayer (Adhan) from the rooftop of the Kaaba — a true symbol of equality in Islam.

He further stated that merely making or changing laws cannot transform social attitudes. “It’s like giving a painkiller to a cancer patient — it may relieve the pain, but it doesn’t cure the disease,” he said. Similarly, caste discrimination cannot be solved through superficial measures. Economic progress, he added, is also insufficient if prejudice remains in people’s hearts. Many Dalits, despite achieving high positions, still face social exclusion and disrespect because the mindset remains unchanged.

Quoting Quranic verses and the sayings of the Prophet ﷺ, Dr. Nadwi reminded that all human beings have been created from one man and one woman — hence, no one can be deemed superior or inferior. Wherever Islam spread, it established equality and justice, inspiring millions to embrace it. “Unfortunately,” he said, “Muslims today have drifted away from these very teachings.”

He disagreed with the claim that the caste system was created by the British, clarifying that “the British did not introduce it; they merely maintained it. The caste structure is thousands of years old and deeply rooted in Indian society.” Dr. Nadwi endorsed Professor Shashi Shekhar’s observation that caste remains a social reality in India. He added that despite urbanization and education, caste consciousness persists even among the educated and urban elite. He also rejected the notion that interfaith marriages could eliminate caste discrimination, saying, “Islam clearly prohibits marriage outside the faith.”

In his inaugural remarks, JIH Delhi president Salimullah Khan said that anyone who reads the Qur’an realizes that human dignity lies in being human. “Mutual respect in society requires reciprocity — if we seek respect, we must also respect others,” he said. “This is possible only when we truly understand one another, as ignorance breeds division.”

ISRD Secretary Asif Iqbal, shedding light on the aims and objectives of the lectures, said that the purpose of this lecture series is not merely academic discussion but “to understand society and engage with it meaningfully.” He added, “Our aim is to study the social fabric of a diverse city like Delhi on a scholarly basis so that we can contribute positively and purposefully.”

Dr. Pradeep Kumar Shinde, Assistant Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, delivered the keynote address. He asserted, “It is extremely difficult to eliminate caste from this country. Caste existed long before the British arrived; however, the British census institutionalized it.” He explained that during the colonial period, the classification of individuals by caste in census records made the system permanent. Before that, caste had only local significance, but after the census, it became a fixed identity defining what one eats, who one marries, and whom one socializes with.

Citing historical references, Dr. Shinde said that Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, in his 1930s lecture “Annihilation of Caste,” made it clear that the caste system originated from Hindu religious texts — a problem absent in Islam and Christianity. He added that although some sociologists argue that untouchability and discrimination have declined, ground realities reveal otherwise.

“Even today,” he said, “we hear of Dalits being denied temple entry or attacked for riding a horse at their wedding. These incidents show that caste bias has not disappeared — it has merely changed its form.”

Referring to recent incidents in Rajasthan, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh, he pointed out that institutions like the police and judiciary — which are supposed to be caste-neutral — often display discriminatory behavior. “In the Hathras case, Dalits had to struggle for days just to file an FIR. This proves that caste bias persists even in bureaucracy and the judiciary.”

Dr. Shinde quoted Dr. Ambedkar’s words that “political power is essential for the annihilation of caste.” Yet today, politics itself is divided along caste lines. “Caste has penetrated every institution and section of society,” he said.

He noted that caste discrimination has now become a global issue. “Dalits in the UK introduced an Anti-Caste Bill — though it was rejected, it brought international attention to the issue. In the U.S., a Dalit engineer woman also filed a caste discrimination complaint.” He added, “To claim that since all are Hindus, caste discrimination will end — is a political illusion meant to divert attention from the real issue.”

Professor Shashi Shekhar of Delhi University, in his address, emphasized that caste is a harsh reality of Indian society. “You can change your religion in India but not your caste, as caste is tied to birth,” he said. For instance, if a man from an upper caste marries a woman from a lower caste, the woman retains her caste-based entitlements, but the child does not — a reflection of patriarchy.

He pointed out that discrimination based on caste persists despite legal and social reforms. Even within castes, sub-castes exist — for example, within Brahmins, there are higher and lower divisions. “The RSS chief, for instance, is a Chitpawan Brahmin, considered among the highest,” he noted.

Education and urbanization, he noted, have weakened the system to some extent, though caste identity remains strong, especially in rural areas and even in cities as a form of political identity. “In classrooms, caste should hold no meaning,” he remarked, “but during university and college elections, caste politics often resurfaces.”